16. Dressed to impress

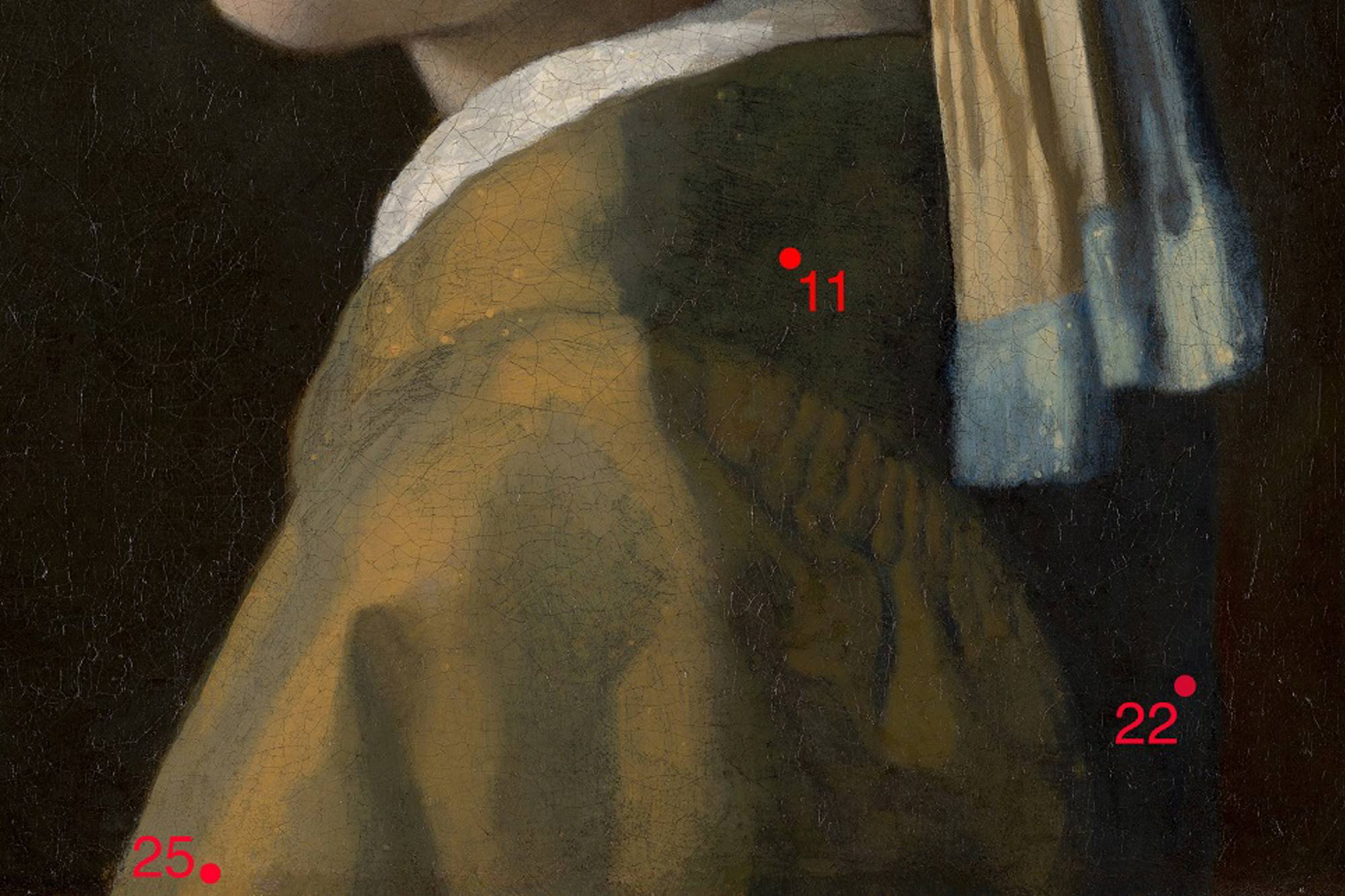

If the Girl stepped onto a red carpet, reporters might ask ‘who are you wearing?’ She is wearing an original Vermeer creation. On top of a white shirt, she has paired a contemporary jacket with a vintage blue and yellow headscarf. The inset sleeve of the jacket has cartridge pleating on the back where it meets the bodice. These are the parallel lines on the back of her shoulder.

Apparently Dutch women wore this kind of jacket around 1660, but the headscarf wasn’t one that people wore around town in Vermeer’s time. It was a costume to give her the appearance of an exotic tronie (character study).

Down-to-earth

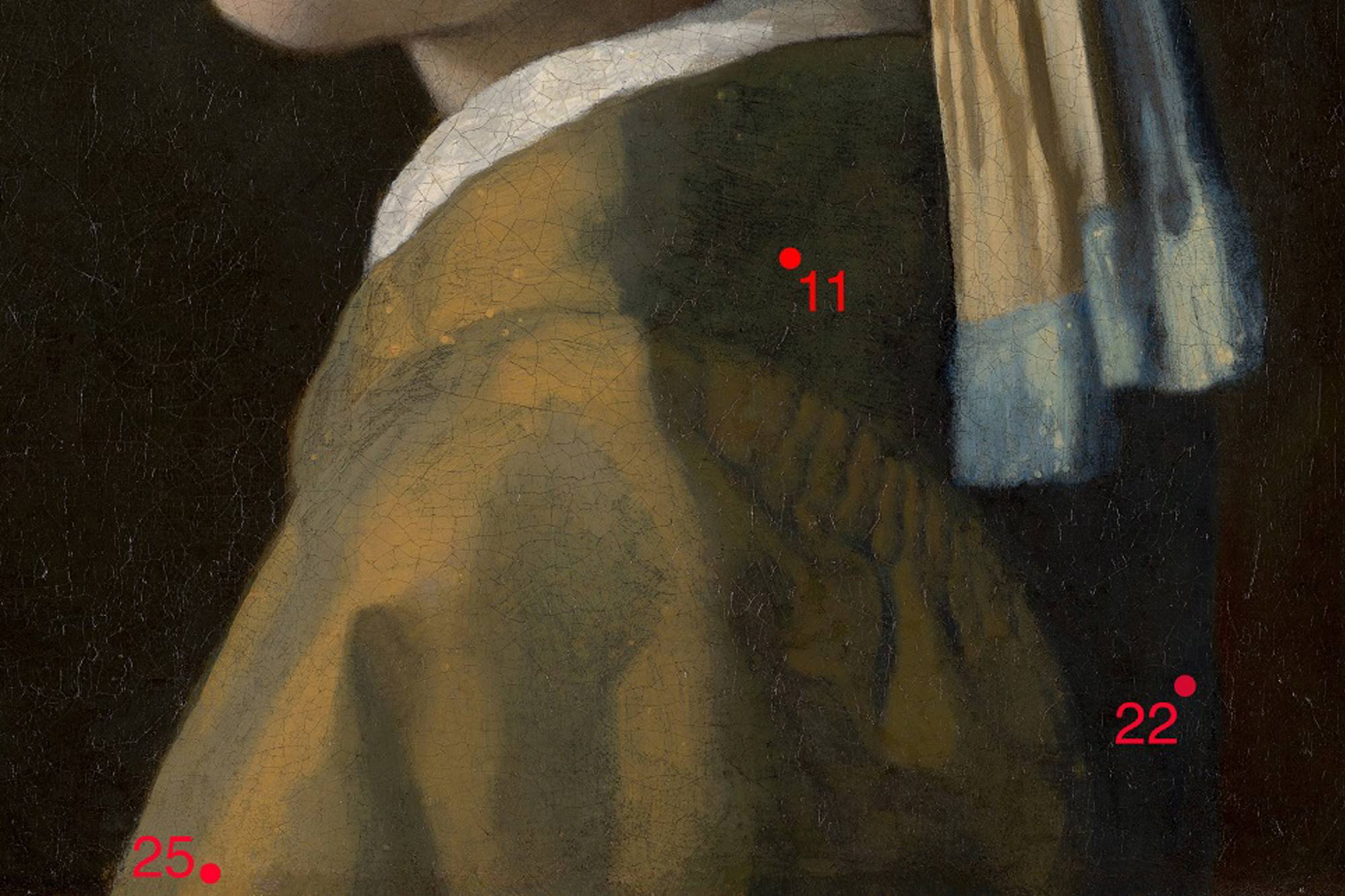

Vermeer used several yellow, red and brown pigments to paint the jacket, and they are collectively known as ‘earth pigments’. Where do they come from? They occur naturally in the earth and are mostly made up of iron oxide. The MA-XRF map for iron (Fe) shows us their distribution within the jacket, with a higher intensity in the pleating and fold behind her shoulder.

Earth pigments can come in different shades – yellow ochre, red ochre, umber, sienna – depending on which other minerals are present. They have been used for hundreds of thousands of years: from cave paintings to coloured grounds for paintings. Deposits of iron oxide occur all over the world. Regions of Italy, France and England have been historically important sources. We can probably assume that Vermeer’s earth pigments came from somewhere close to home, although apparently high-quality earths for making pigments were transported over long distances.

To turn natural earth into a pigment, you need to wash it to the remove mineral impurities, then grind it into to a fine powder. Some earths were processed even further. For example, you can make a red earth by burning (calcining) a yellow earth in a clay pot over a red-hot fire.

Making a paint with earth pigments takes a lot of oil because the pigments absorb a great deal of binding medium. The paint also dries fast, sometimes within a couple of hours. This allowed Vermeer to work relatively quickly on the Girl’s clothing.

Mellow yellow

What colour was the Girl’s jacket meant to be – yellow, yellowish-brown, yellowish-green, yellowish-blue? The answer is ‘all of the above.’ Vermeer's choice of different tones created a 3-dimensional, real-looking appearance. He used several strategies to differentiate the highlights, midtones and shadows in the jacket:

Download Image

Non-commercial use

All our images can be downloaded in high resolution from our website for non-commercial use (research/study, educational purposes, personal blogs and social media).

Would you like to use our images in a publication? Please mention our credit line: "Mauritshuis, The Hague."

Commercial use

Would you like to use our images for commercial purposes? We would be happy to discuss this with you. Please contact our marketing department at [email protected].

Download Image

Non-commercial use

All our images can be downloaded in high resolution from our website for non-commercial use (research/study, educational purposes, personal blogs and social media).

Would you like to use our images in a publication? Please mention our credit line: "Mauritshuis, The Hague."

Commercial use

Would you like to use our images for commercial purposes? We would be happy to discuss this with you. Please contact our marketing department at [email protected].

Download Image

Non-commercial use

All our images can be downloaded in high resolution from our website for non-commercial use (research/study, educational purposes, personal blogs and social media).

Would you like to use our images in a publication? Please mention our credit line: "Mauritshuis, The Hague."

Commercial use

Would you like to use our images for commercial purposes? We would be happy to discuss this with you. Please contact our marketing department at [email protected].

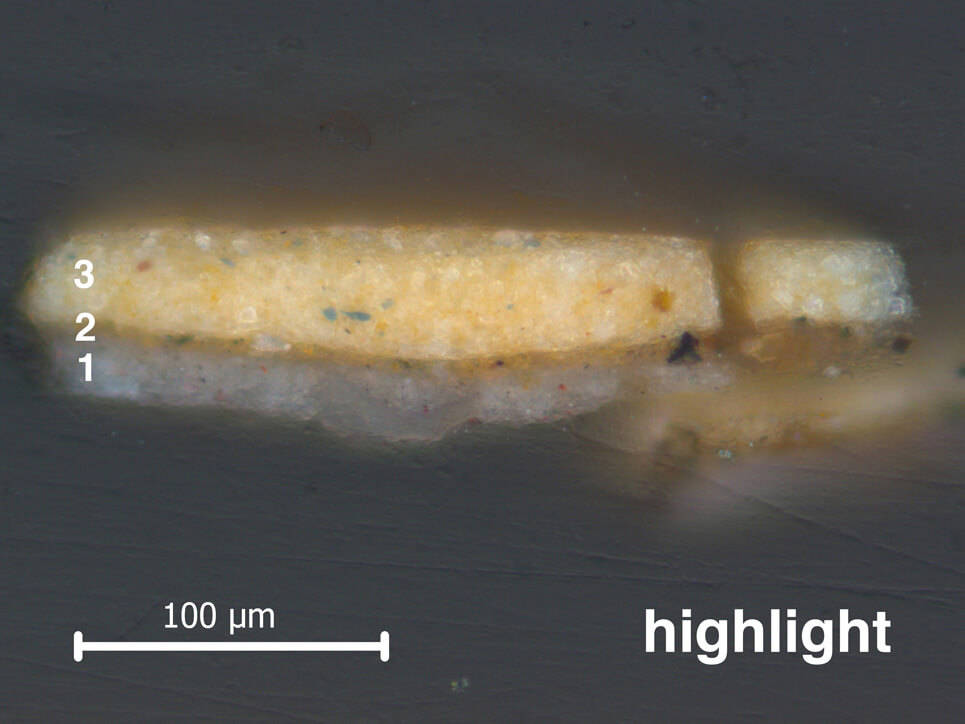

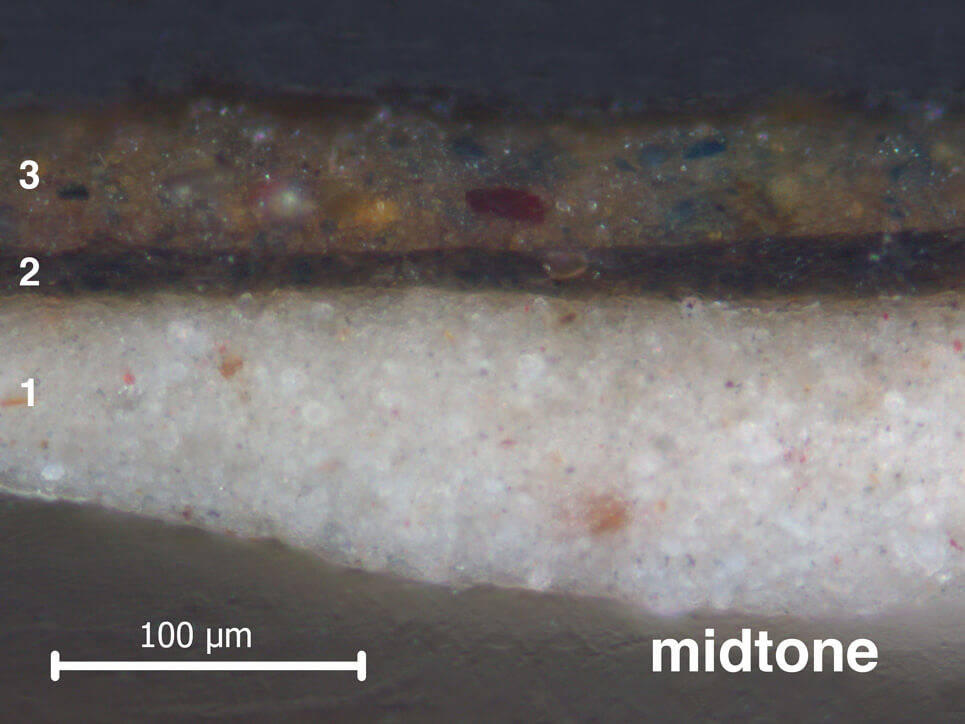

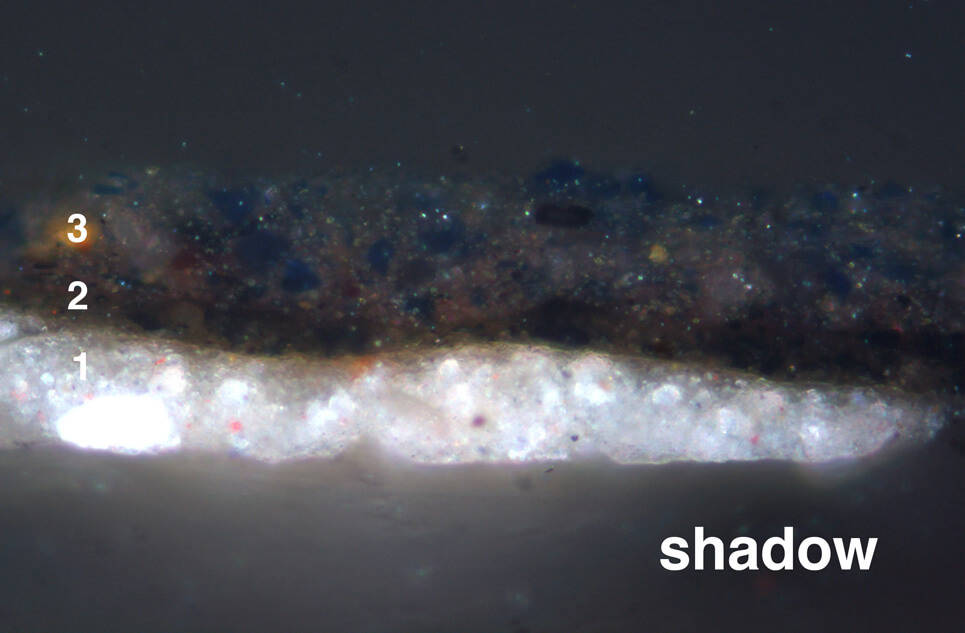

Vermeer started painting the jacket by laying in where the light and dark tones were to go. He painted this ‘dead colouring’ in different shades of brown. In the cross-sections from the Girl’s jacket, the underlayer used for dead colouring (layer 2) varies in tone and thickness depending on whether it is in the light or the shadow. Beneath the highlight, this layer is thin and light brown. Below the midtone and shadow, it is thick and dark brown.

When the brown ‘dead colouring’ was dry, Vermeer applied only one layer of paint on top (layer 3). In some areas on her jacket – like the cartridge pleats on the back of her shoulder – he left the underlayer to shimmer through. The underlayer on her back contains carbon black, which can be detected using infrared. In the infrared photograph of her shoulder, you can see that Vermeer applied it with a wide brush.

Another way that Vermeer created different tones in the jacket was to mix the earth pigments with other colours in different quantities. In the highlight, he mixed the yellow ochre with lead white, and a little bit of ultramarine blue. This yellow mixture would have been opaque. To create the midtones and shadows, Vermeer mixed in more ultramarine blue, added red lake and left out the lead white. This mixture would be more transparent than the highlight, and would let the colour of the dark underlayer shimmer through. This is why the back of her shoulder looks greenish-blue.

Mixing ultramarine into the shadows seems like a waste of what would have been an expensive pigment! But as I’ll describe tomorrow, Vermeer was known to have used ultramarine extensively, even in seemingly unimportant areas of his paintings.

References

- Broos, B.P.J., Ariane van Suchtelen and Quentin Buvelot (1999) Portraits in the Mauritshuis: 1430-1790, Wbooks, pp. 259-262.

- Helwig, Kate (2007) ‘Iron oxide pigments: Natural and synthetic.’ In: Artists’ Pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, Barbara H. Berrie (ed.), Vol. 4, National Gallery of Art, Washington and Archetype, London, pp. 39-95.

- Janson, Jonathan ‘Dead colouring or underpainting,’ Essential Vermeer

Acknowledgements

- Costume specialist: Marieke de Winkel

- Light microscopy, SEM-EDX, MA-XRF scanning: Annelies van Loon (Mauritshuis / Rijksmuseum)

- SEM-EDX: Ralph Haswell (Shell Technology Centre Amsterdam)

- Infrared reflectogram: René Gerritsen (René Gerritsen Art & Research Photography)

- MA-XRF: Annelies van Loon (Mauritshuis/Rijksmuseum)