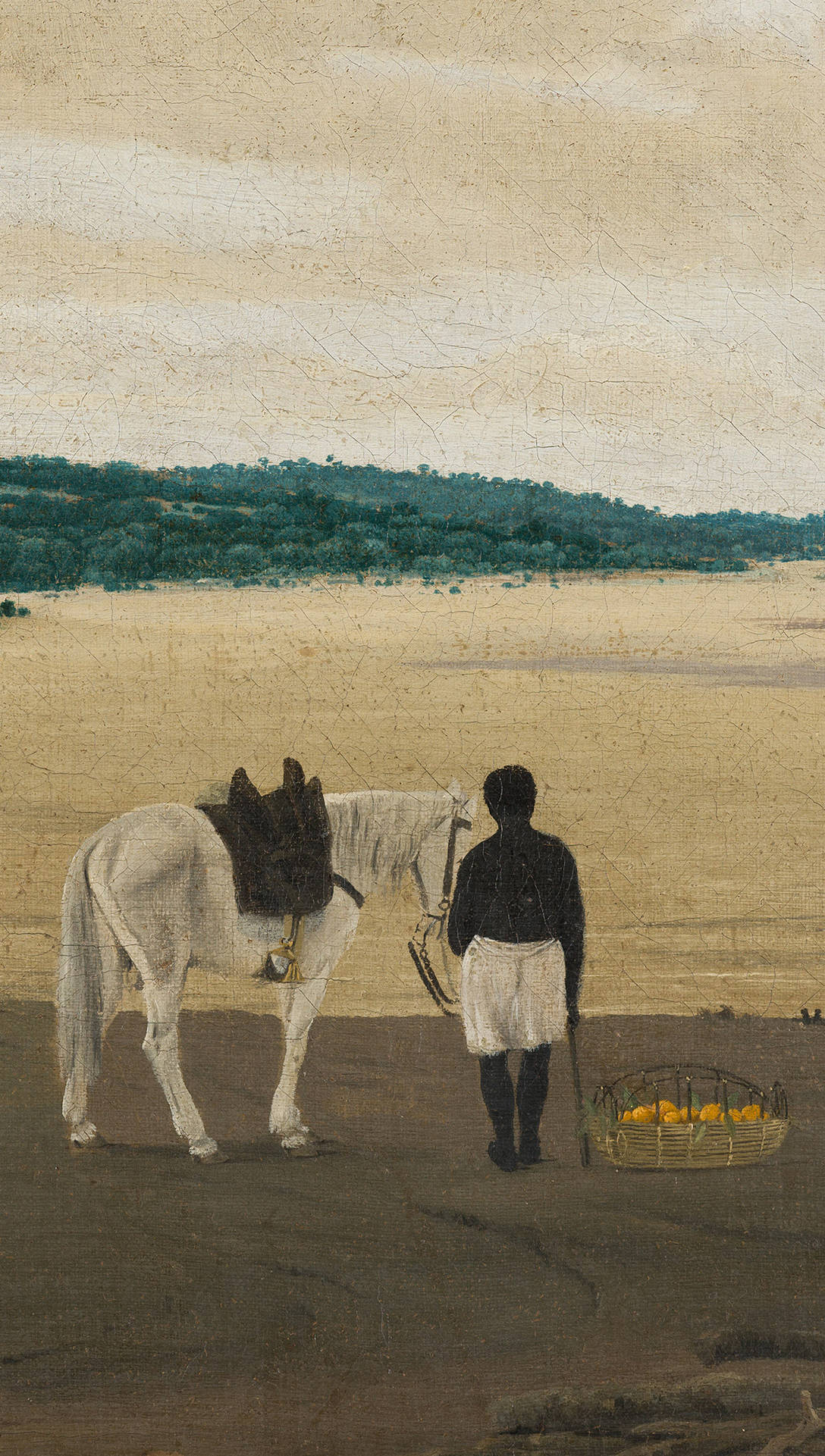

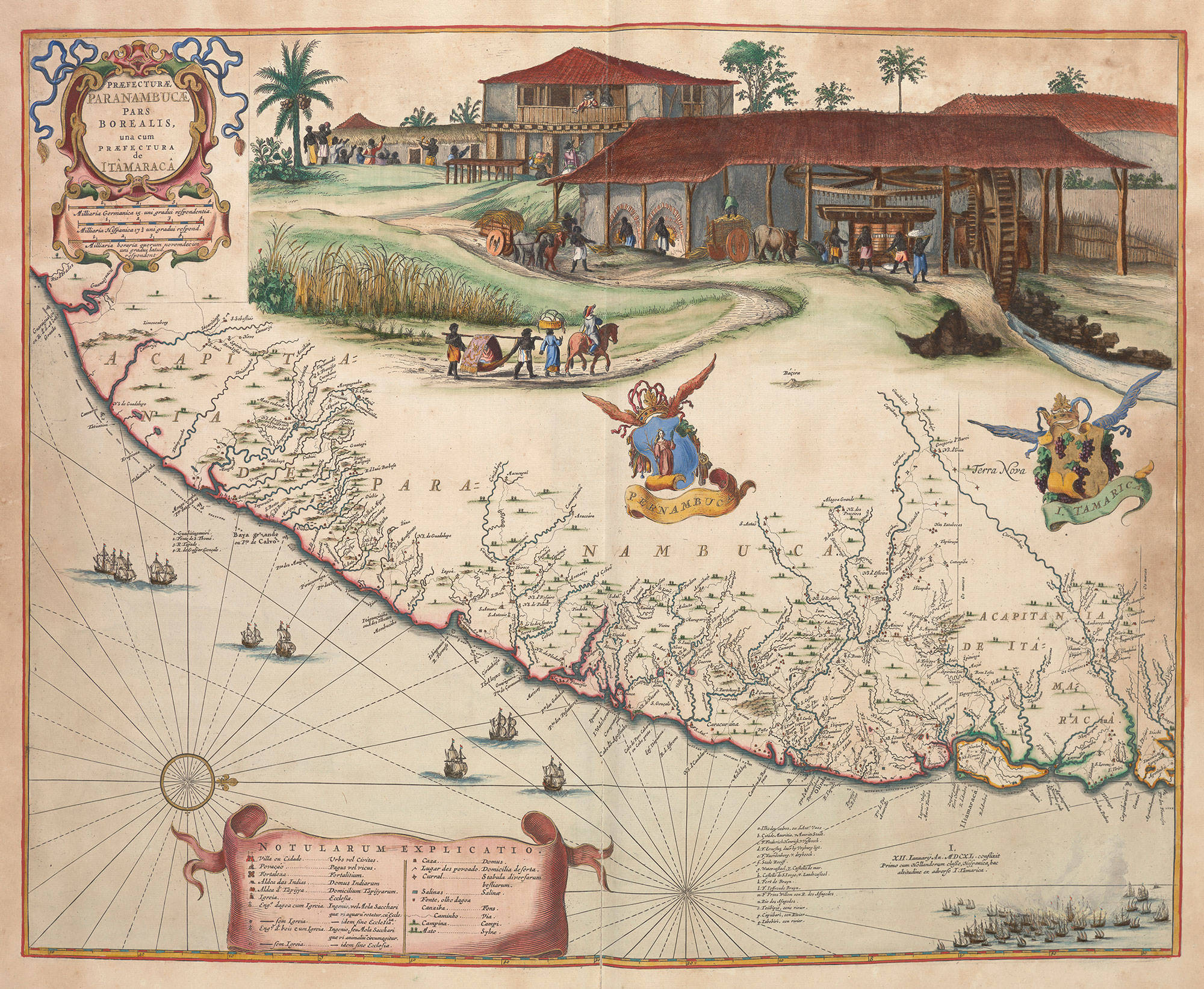

Johan Maurits worked as governor of Dutch Brazil in the service of the WIC for around seven years. When he left for Brazil in 1636, he not only took soldiers with him, but scientists and artists too. They produced paintings, drawings and scientific studies of the country, its inhabitants and natural habitat. These artworks and books are still extremely important for our understanding of Brazil in the 17th century. However, the colony didn’t revolve around science and art: Dutch Brazil was a plantation colony that was captured by the Dutch for its sugar industry. The hard work on the sugar cane plantations wasn’t done by the Dutch themselves – enslaved Africans were used for this instead. Johan Maurits sent warships to the African Gold Coast (Ghana) and Angola, where his troops captured two large Portuguese slave forts. In doing so, Johan Maurits paved the way for the Dutch contribution to the trade and transport of enslaved people to the Americas. During his seven-year governorship, at least 24,000 men, women and children were transported to Dutch Brazil. Many didn’t survive the journey.

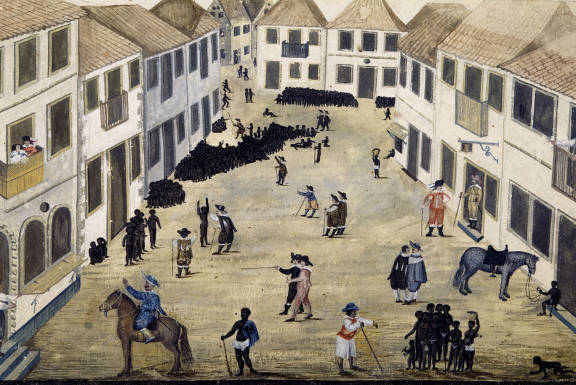

Johan Maurits himself owned dozens of enslaved people, who he branded with his monogram. This is visible in a drawing of this woman, who bears Johan Maurits’s mark on her chest. The slave market in Mauritsstad (today’s Recife), where Africans were traded, also appears in another drawing by the same person. These drawings are rare 17th-century examples in which the inhuman reality of slavery and the trade in people is visible.

Johan Maurits was well paid by the WIC for his role as governor. But he also had other sources of income. We recently learned that he traded in enslaved people for personal gain. He smuggled people into the country on ships flying the Portuguese flag. Among other things, he used his Brazilian earnings to build the Mauritshuis. Which is why, as early as the 17th century, the building gained the nickname ‘the Sugar Palace’.